Overview

The heart is a muscular pump that pushes blood throughout the entire body. In a normal dog, it beats approximately 150,000 times a day. The pericardium is a membrane that envelopes the heart. It has two layers: a thin, inner layer that adheres to the heart muscle, and a thicker outer layer that is a fibrous, rather tough sac. The space between the two layers, called the “pericardial space,” normally contains a small amount of fluid. If the fluid accumulates in the pericardial space to such an extent that it prohibits the heart from pumping properly, heart disease and even failure can result.

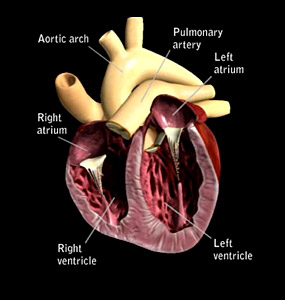

The heart has four chambers, as shown in the illustration below. Like many mechanical pumps, the heart has two functional parts. The atria, which are the thin-walled chambers labeled “left atrium” and “right atrium,” act as pump primers. Blood returning to the heart is held here and, when the atria are full, they contract, pushing blood into the pumping chambers or ventricles. When full, these pumping chambers contract forcefully, pushing blood out to all the blood vessels in the body.

You’ll see that the heart is actually made up of two pumps, labeled right and left, based on their anatomic position in the body. So we have one pump made up of the right atrium and right ventricle and one made up of the left atrium and left ventricle. Valves between the atrium and the ventricle ensure blood always moves in one direction, from the atrium into the ventricle. The heart is made up of two pumps because our pets’ bodies, like ours, have two different circuits for blood flow, moving first through one and then the other. One of these circuits takes blood through the lungs so that oxygen can be replenished and waste gases, like carbon dioxide, are removed. This oxygen-enriched blood then moves through the other circuit, reaching all parts of the body to deliver the oxygen needed for normal body function and removing any waste products produced as a consequence.

You’ll see that the heart is actually made up of two pumps, labeled right and left, based on their anatomic position in the body. So we have one pump made up of the right atrium and right ventricle and one made up of the left atrium and left ventricle. Valves between the atrium and the ventricle ensure blood always moves in one direction, from the atrium into the ventricle. The heart is made up of two pumps because our pets’ bodies, like ours, have two different circuits for blood flow, moving first through one and then the other. One of these circuits takes blood through the lungs so that oxygen can be replenished and waste gases, like carbon dioxide, are removed. This oxygen-enriched blood then moves through the other circuit, reaching all parts of the body to deliver the oxygen needed for normal body function and removing any waste products produced as a consequence.

So long as it is healthy, the pericardium has no real effect on basic heart function other than providing protection and lubrication. When diseased, however, it can have a significant influence and cause severe, sometimes life-threatening conditions. The most common conditions that affect the pericardium are inflammation and cancer. Either one of these problems can lead to excessive production of fluid within the pericardial space, which, as mentioned, usually contains only a small amount of fluid. If the excess fluid production occurs slowly, the pericardium can stretch—up to a point. If there is a rapid accumulation, there is no time for the stretching to occur. In either case, excess fluid accumulation will cause the pressure to rise inside the pericardial sac and, ultimately, to compress the heart. This can be devastating, because it will prevent the return of blood into the heart. If the blood can’t get in, then it can’t be pumped out either. There are two main consequences. The blood that can’t get back in will start to leak fluid, mainly into the abdomen. The decrease in blood being pumped out means the muscles and organs don’t get the blood they need, and your pet will become progressively weaker. This process can occur very quickly or slowly, depending on the rate at which the fluid is accumulating in the pericardial space and how quickly the pressure within the sac is rising. This accumulation of fluid within the sac is called “pericardial effusion.”

Pericardial disease can occur in any dog, but is more common in larger breeds, especially the golden retriever, where it is often associated with cancer. Pericardial disease is considered rare.

Symptoms

Symptoms are caused by the two phenomena described above: an inadequate amount of blood returning to the heart and an inadequate amount being pumped out. The blood that can’t get back into the heart starts to leak fluid, which will accumulate in unusual places. When pericardial effusion is the cause, the most likely place for this fluid to accumulate is in the abdomen. You may notice your pet’s abdomen becoming plumper. This will occur at a much faster rate than you would see if your pet was gaining weight due to his diet! Blood that can’t get back into the heart can’t be pumped out to supply the muscles and organs with the blood they need, so your pooch will become weak and lethargic.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The first thing that your veterinarian might notice is an inability to hear your pet’s heart. The fluid in the sac blocks sound transmission, effectively suppressing the lubb-dupp that would normally be heard. If pericardial disease is suspected, your veterinarian will typically recommend a number of different tests:

- A radiograph, commonly known as an x-ray

- A blood test for a cardiac biomarker called NTproBNP

- A complete blood count (CBC) and chemistry profile to assess the state of all the organs

- A blood pressure test

- An ECG (electrocardiograph) to record the electrical action in your dog’s heart

- An echocardiogram to take a look at your pet’s heart structure and function using ultrasound. This is especially important with pericardial disease as it can help identify if cancer is the cause.

If your dog is diagnosed with pericardial disease, your veterinarian will consider the following points in determining the best treatment for your pet:

- The best way to treat this disease is to remove the fluid from the pericardial sac as quickly as possible. A catheter is placed into the pericardial sac and the fluid removed with a syringe. To keep your pet comfortable, sedatives and local anesthesia might be used during this process.

- After the fluid is removed, your veterinarian may give a short course of a diuretic to clear the fluid that has accumulated in your dog’s abdomen.

- Long-term management depends on the underlying cause.

- If a cancer is diagnosed, therapy will be aimed at managing that disease.

- In some pets, the cause of the pericardial effusion may not be determined, and only one episode of the disease is seen.

- In others, chronic inflammation can occur, leading to repeat episodes of pericardial effusion. If this happens, your veterinarian may recommend a surgical procedure to remove a portion of your pet’s pericardium, to help prevent further occurrences.

Prevention

Unfortunately, there is nothing that can be done to prevent pericardial disease. Early detection and recognition of pericardial effusion as a cause of the symptoms described above is the best way to manage your pet, should he develop this rare, but potentially fatal, disease.

If you have any questions or concerns, you should always visit or call your veterinarian – they are your best resource to ensure the health and well-being of your pets.